PROFILE: Flynns remain in Rutledge for over 100 years

Published 2:36 pm Thursday, April 7, 2016

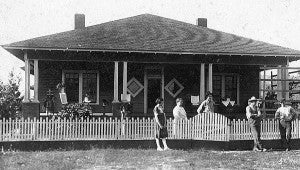

From left (top), Flynn Gregory, Ikey Gregory, Connie Lorraine Garmon, Kevin Christian and Alexis Lorraine Christian, and (bottom) Christian Garmon, Hazel Lorraine Flynn Gregory and Fran Lorraine Christian in front of the second home built on the family’s land in 1921, current home to Hazel Gregory.

The following article was part of the Profile 2016 special section of The Luverne Journal. The section in its entirety can be found in the March 31 edition of The Luverne Journal.

SPECIAL TO THE JOURNAL: SAVANAH WEED

The Flynn family has lived on the same plot of land in Rutledge, Ala., for over 100 years.

The Flinns, as they spelled it at the time, did not have an easy start to life in Crenshaw County. In 1865, Matilda Flinn lost her husband, a Confederate soldier named Robert, to an unknown illness and lost her farm near Louisville, Ala., in a raid done by Yankee soldiers.

“Even with an empty corncrib, an empty smokehouse, no cow and nothing left to plant, Matilda and her children survived the year,” said Clara Campbell Turner, now 82, Matilda’s great-granddaughter.

The year that Rutledge became the first seat of Crenshaw County, 1866, Matilda moved herself and three sons — John, 12, William, 11 and Robert, seven— there from Barbour County.

“So Matilda was reconstructing her own personal and family life while Crenshaw County was being constructed, while Rutledge was being constructed and while the entire Confederate South was being reconstructed,” Turner said. “There was no money, no help in the fields. The necessities of life were hard to come by.”

In 1883, William D. Flinn married Clara McGehee, and the pair moved into Matilda’s house, the first Flinn home on the 315-acre plot.

“They lived their entire married life in Ma’s house on Ma’s land,” Turner said. “They were also very good at making babies.”

They had 11 children: Willie, Mattie, Irene, Roy, Henry, Susie, Myrtle, Walter, Ruby Belle, Joe and Ida Mae.

Joe Flynn married Linnie Belle Powell in 1919; together, they had three children named Hazel Lorraine, Joe Harold and Joe Douglas.

With so many children coming into an already large family, space was sparse in the Flinn household.

“My grandfather was reported to have said that he wanted my momma and daddy out of his home,” said Hazel Lorraine Flynn Gregory, 94. “So he came up here and built this house, and it was intended for me to be born in it.”

This was the second house built on the Flinn property; it was completed during the summer of 1921, and Gregory was born only a few months later on Nov. 1. A popular story among members of the family is that the house was built using the trees from the land.

“Poppa floated the trees from the land down the river to Brantley and sent wagons to bring the lumber back,” she said. “There’s no telling where the lumber actually came from, but that’s what they say.”

There are now a total of eight Flynn homes spread across the land that was passed down to Gregory.

“Three doors down is where my grandson lives,” Gregory said. “That is the original McGehee, my grandmother’s, house.”

Gregory’s grandfather married his wife in the living room of the McGehee house; their honeymoon was the walk down Alabama Highway 10 — commonly known as Lee Street — between that house and their new home: the original house of Matilda Flinn.

“There was no highway then,” she added, “just a dirt road.”

The same road that served as witness to her grandparents’ blissful honeymoon walk saw the sadness of the Great Depression.

“I do recall people coming down that dusty road,” she said. “One instance I specifically recall because it affected me so much as a child.

“There was a man and his wife, and they held a child by the hand. My momma had me run out and tell them to come in, and then she fed them and packed them a bag.” Her father gave them a ride to the main road and trusted someone else to help from there.

“Everyone helped,” she added. “You just did.”

It was also Gregory’s parents who would cause the spelling of their last name to be changed.

When Gregory was four years old, she and her mother went to live in Florida.

“I remember Momma writing back and forth, and instead of ‘i,’ she and Uncle Roy’s wife Lucy wrote back and they would invariably spell it ‘Flynn,’ ” she said.

According to Gregory, the “i” side was looked on as “highfalutin,” and her mother and the other wives considered themselves to be “fruit-pickers’ ” wives.

“And to this day we are still ‘y,’ ” she said. “We’re still the country folks.”

Not only did this family see through the Great Depression; they also saw the beginnings of the civil rights movement.

“My husband was one of the first white principals of the colored schools when they began to integrate,” she said. When school officials began searching for white teachers to be put into these schools, not many were willing.

“My daughter and her husband and my son and his wife were the only ones that agreed,” she added. “So they went, and they taught.”

Hazel Flynn and Bill Gregory, who was stationed with the military in Selma at the time, met through a mutual friend in Luverne and were married July 4, 1941, in a pastor’s living room in Montgomery.

“One of his friends got in touch with him and told him, ‘Hey, you’re supposed to be on duty!’ ” she said. When they arrived at the base in Selma, his unit surprised them and had their picture made.

She and her husband eventually moved into a one-bedroom apartment in Selma for $18 a month. “And that included lights, water and gas,” she explained. They lived off $100 a month.

“You could get a whole thing of groceries, everything you could possibly need for a month, at most, at the highest, for $25,” she said. Instead of shopping at grocery stores, she would sometimes shop at the commissary on base, where he would meet her afterward and walk her home.

Gregory spent a few years away from her childhood home on Lee Street, leaving again only for college, work and a stay with her husband in Selma. When they inherited her parents’ home, there were only five rooms, and changes were needed to accommodate their two children, Flynn and Fran Lorraine.

Clara Flinn (fourth from the left) and her seven daughters at the family home. The daughters (not necessarily in the order shown here) were Mattie, Irene, Susie, Myrtle, Ruby, Belle and Ida Mae.

“We added a little small bedroom and the bath,” she said. “We raised our family here.”

“There were no bathrooms here,” added Connie Lorraine Garmon, Gregory’s granddaughter, “just outhouses.”

Not only was the exterior changed, but the interior underwent a makeover as well.

Bookshelves filled with old novels and family albums line the hallway, and pictures of family fill every available space. A portrait of the USS Constitution hangs at the end of the hallway; its frame is made from the wood of the real ship.

The living room even features three original parchment paintings from the Japanese Dark Age period.

“My husband’s uncle wrapped those up and snuck them out of Japan,” Gregory said. “The Gregorys had them framed and gave them to me and Bill.”

Antique lamps, dressers and knickknacks passed down through the generations are everywhere; stepping through the front door is like stepping back in time.

“On one side of the porch is the landmark plow,” Garmon said, “the original plow that was used to plow the land when they first moved here.” The house even still has the original two-piece candlestick, built-in phone; however, it now functions as a resting place for photos of grandchildren and a plastic elephant head.

Garmon recalls she and her cousins being close; she said they were always running from one house to another, playing games and watching the men work in the field.

“I wish my kids could have had the same like I did,” she said.

The farm is no longer fully functional. Gregory’s great nephew, Brock Flynn, now takes care of only the cattle.

“He has done well,” Gregory smiled, “even though every once in a while he comes dragging in at church and he looks like he’s been dragged through the mud.”

His son, Sawyer, has been following him and learning about how to care for the cattle since he was a year old, Garmon joked.

“I feel like the Flynn place will continue on down the line,” Gregory said.